Zinc for COVID-19: real-time meta analysis of 28 studies

Covid Analysis, April 10, 2022

Share Tweet Studies Submit Feedback

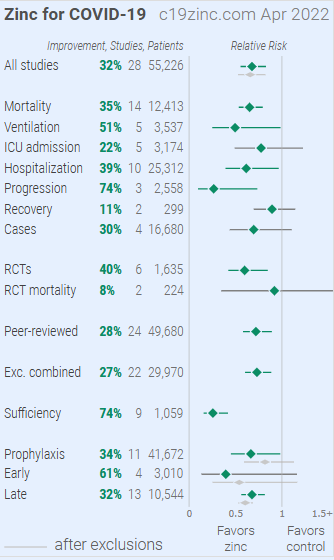

Statistically significant improvements are seen for mortality, ventilation, hospitalization, and progression. 11 studies from 11 independent teams in 6 different countries show statistically significant improvements in isolation (8 for the most serious outcome).

•Meta analysis using the most serious outcome reported shows 32% [17‑45%] improvement. Results are similar for Randomized Controlled Trials, similar after exclusions, similar for peer-reviewed studies, and similar after excluding studies using combined treatment. Early treatment is more effective than late treatment.

•Sufficiency studies, analyzing outcomes based on serum levels, show 74% [58‑84%] improvement for patients with higher zinc levels (9 studies).

•Results are robust — in exclusion sensitivity analysis 11 of 28 studies must be excluded to avoid finding statistically significant efficacy in pooled analysis.

•6 studies use combined treatments. When excluding those studies, the pooled improvement is 27% [11‑40%] compared to 32% [17‑45%].

•Early treatment results are dominated by [Thomas], however this study used a low dose and was conducted in a location with low levels of zinc deficiency.

•While many treatments have some level of efficacy, they do not replace vaccines and other measures to avoid infection. Only 11% of zinc studies show zero events in the treatment arm. Multiple treatments are typically used in combination, and other treatments may be more effective.

•No treatment, vaccine, or intervention is 100% available and effective for all variants. All practical, effective, and safe means should be used. Denying the efficacy of treatments increases mortality, morbidity, collateral damage, and endemic risk.

•All data to reproduce this paper and sources are in the appendix.

Zinc reduces risk for COVID-19 with very high confidence for mortality and in pooled analysis, high confidence for ventilation, hospitalization, and progression, and very low confidence for cases.

We show traditional outcome specific analyses and combined evidence from all studies, incorporating treatment delay, a primary confounding factor in COVID-19 studies.

Real-time updates and corrections, transparent analysis with all results in the same format, consistent protocol for 40 treatments.

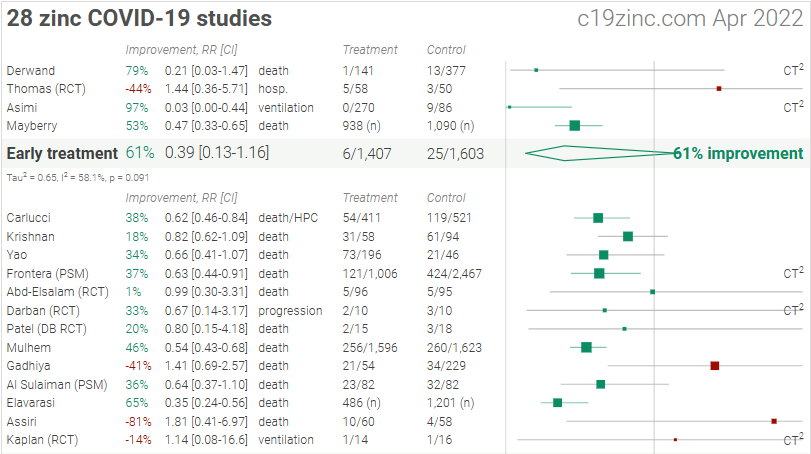

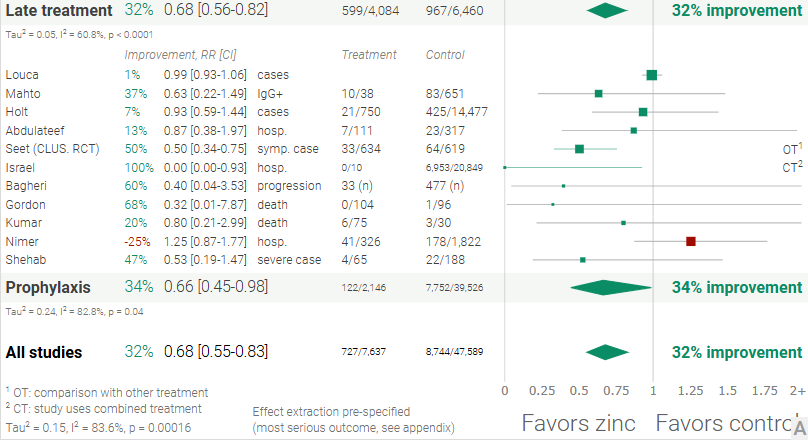

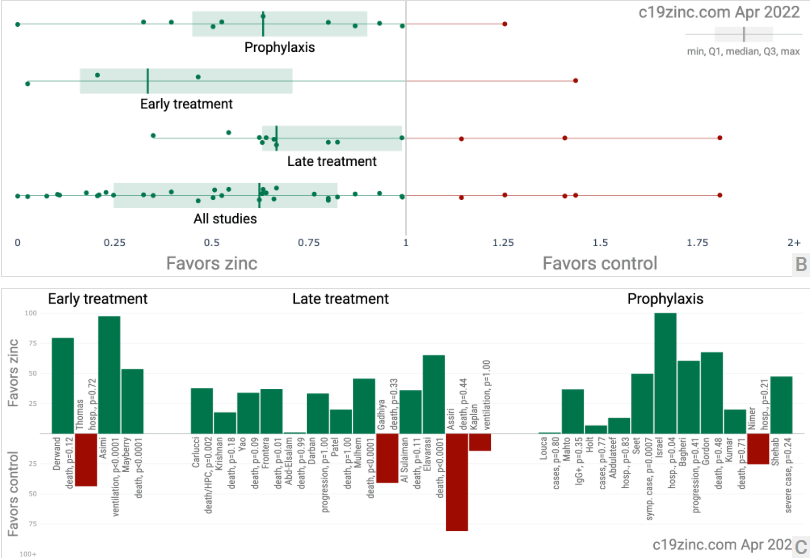

Figure 1. A. Random effects meta-analysis. This plot shows pooled effects, discussion can be found in the heterogeneity section, and results for specific outcomes can be found in the individual outcome analyses. Effect extraction is pre-specified, using the most serious outcome reported. For details of effect extraction see the appendix. B. Scatter plot showing the distribution of effects reported in studies. C. History of all reported effects (chronological within treatment stages).

Introduction

We analyze all significant studies concerning the use of zinc for COVID-19. Search methods, inclusion criteria, effect extraction criteria (more serious outcomes have priority), all individual study data, PRISMA answers, and statistical methods are detailed in Appendix 1. We present random effects meta-analysis results for all studies, for studies within each treatment stage, for individual outcomes, for peer-reviewed studies, for Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), and after exclusions.

Figure 2 shows stages of possible treatment for COVID-19. Prophylaxis refers to regularly taking medication before becoming sick, in order to prevent or minimize infection.

Early Treatment refers to treatment immediately or soon after symptoms appear, while Late Treatment refers to more delayed treatment.

Results

Figure 3 shows a visual overview of the results, with details in Table 1 and Table 2. Figure 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14 show forest plots for a random effects meta-analysis of all studies with pooled effects, mortality results, ventilation, ICU admission, hospitalization, progression, recovery, cases, sufficiency studies, peer reviewed studies, and all studies excluding combined treatment studies.

Figure 3. Overview of results.

| Treatment time | Number of studies reporting positive effects | Total number of studies | Percentage of studies reporting positive effects | Random effects meta-analysis results |

| Early treatment | 3 | 4 | 75.0% | 61% improvement RR 0.39 [0.13 1.16] p = 0.091 |

| Late treatment | 10 | 13 | 76.9% | 32% improvement RR 0.68 [0.56 0.82] p < 0.0001 |

| Prophylaxis | 10 | 11 | 90.9% | 34% improvement RR 0.66 [0.45 0.98] p = 0.04 |

| All studies | 23 | 28 | 82.1% | 32% improvement RR 0.68 [0.55 0.83] p = 0.00016 |

Table 1. Results by treatment stage.

| Studies | Early treatment | Late treatment | Prophylaxis | Patients | Authors | |

| All studies | 28 | 61% [-16 87%] | 32% [18 44%] | 34% [2 55%] | 55,226 | 293 |

| With exclusions | 18 | 46% [-16 75%] | 40% [31 47%] | 18% [-13 41%] | 14,226 | 194 |

| Peer-reviewed | 24 | 46% [-16 75%] | 25% [7 40%] | 34% [2 55%] | 49,680 | 238 |

| Randomized Controlled Trials | 6 | -44% [-471 64%] | 14% [-90 61%] | 50% [25 66%] | 1,635 | 68 |

Exclusions

To avoid bias in the selection of studies, we analyze all non-retracted studies. Here we show the results after excluding studies with major issues likely to alter results, non-standard studies, and studies where very minimal detail is currently available. Our bias evaluation is based on analysis of each study and identifying when there is a significant chance that limitations will substantially change the outcome of the study. We believe this can be more valuable than checklist-based approaches such as Cochrane GRADE, which may underemphasize serious issues not captured in the checklists, overemphasize issues unlikely to alter outcomes in specific cases (for example, lack of blinding for an objective mortality outcome, or certain specifics of randomization with a very large effect size), or be easily influenced by potential bias. However, they can also be very high quality.

The studies excluded are as below. Figure 15 shows a forest plot for random effects meta-analysis of all studies after exclusions.

[Abdulateef], unadjusted results with no group details.

[Asimi], excessive unadjusted differences between groups.

[Assiri], unadjusted results with no group details.

[Gadhiya], substantial unadjusted confounding by indication likely.

[Holt], significant unadjusted confounding possible.

[Israel], treatment or control group size extremely small.

[Krishnan], unadjusted results with no group details.

[Kumar], unadjusted results with no group details.

[Mulhem], substantial unadjusted confounding by indication likely, substantial confounding by time likely due to declining usage over the early stages of the pandemic when overall treatment protocols improved dramatically.

[Shehab], unadjusted results with no group details.

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

Figure 16 shows the distribution of results for Randomized Controlled Trials and other studies, and a chronological history of results. Figure 17 and 18 show forest plots for a random effects meta-analysis of all Randomized Controlled Trials and RCT mortality results. Table 3 summarizes the results.

RCTs help to make study groups more similar, however they are subject to many biases, including age bias, treatment delay bias, severity of illness bias, regulation bias, recruitment bias, trial design bias, followup time bias, selective reporting bias, fraud bias, hidden agenda bias, vested interest bias, publication bias, and publication delay bias [Jadad], all of which have been observed with COVID-19 RCTs.

RCTs have a bias against finding an effect for interventions that are widely available — patients that believe they need the intervention are more likely to decline participation and take the intervention. This is illustrated with the extreme example of an RCT showing no significant differences for use of a parachute when jumping from a plane [Yeh]. RCTs for zinc are more likely to enroll low-risk participants that do not need treatment to recover, making the results less applicable to clinical practice. This bias is likely to be greater for widely known treatments. Note that this bias does not apply to the typical pharmaceutical trial of a new drug that is otherwise unavailable.

Evidence shows that non-RCT trials can also provide reliable results. [Concato] find that well-designed observational studies do not systematically overestimate the magnitude of the effects of treatment compared to RCTs. [Anglemyer] summarized reviews comparing RCTs to observational studies and found little evidence for significant differences in effect estimates. [Lee] shows that only 14% of the guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America were based on RCTs. Evaluation of studies relies on an understanding of the study and potential biases. Limitations in an RCT can outweigh the benefits, for example excessive dosages, excessive treatment delays, or Internet survey bias could have a greater effect on results. Ethical issues may also prevent running RCTs for known effective treatments. For more on issues with RCTs see [Deaton, Nichol].

In summary, we need to evaluate each trial on its own merits. RCTs for a given medication and disease may be more reliable, however they may also be less reliable. For example, consider trials for an off-patent medication, very high conflict of interest trials may be more likely to be RCTs (and more likely to be large trials that dominate meta analyses).

Figure 18. Random effects meta-analysis for RCT mortality results. Effect extraction is pre-specified, using the most serious outcome reported, see the appendix for details.

| Treatment time | Number of studies reporting positive effects | Total number of studies | Percentage of studies reporting positive effects | Random effects meta-analysis results |

| Randomized Controlled Trials | 4 | 6 | 66.7% | 40% improvement RR 0.60 [0.42 0.85] p = 0.0039 |

| RCT mortality results | 2 | 2 | 100% | 8% improvement RR 0.92 [0.35 2.44] p = 0.87 |

Table 3. Randomized Controlled Trial results.

Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity in COVID-19 studies arises from many factors including:

Treatment delay.

The time between infection or the onset of symptoms and treatment may critically affect how well a treatment works. For example an antiviral may be very effective when used early but may not be effective in late stage disease, and may even be harmful. Oseltamivir, for example, is generally only considered effective for influenza when used within 0-36 or 0-48 hours [McLean, Treanor]. Figure 19 shows a mixed-effects meta-regression for efficacy as a function of treatment delay in COVID-19 studies from 40 treatments, showing that efficacy declines rapidly with treatment delay. Early treatment is critical for COVID-19.

Patient demographics.

Details of the patient population including age and comorbidities may critically affect how well a treatment works. For example, many COVID-19 studies with relatively young low-comorbidity patients show all patients recovering quickly with or without treatment. In such cases, there is little room for an effective treatment to improve results (as in [López-Medina]).

Effect measured.

Efficacy may differ significantly depending on the effect measured, for example a treatment may be very effective at reducing mortality, but less effective at minimizing cases or hospitalization. Or a treatment may have no effect on viral clearance while still being effective at reducing mortality.

Variants.

There are many different variants of SARS-CoV-2 and efficacy may depend critically on the distribution of variants encountered by the patients in a study. For example, the Gamma variant shows significantly different characteristics [Faria, Karita, Nonaka, Zavascki]. Different mechanisms of action may be more or less effective depending on variants, for example the viral entry process for the omicron variant has moved towards TMPRSS2-independent fusion, suggesting that TMPRSS2 inhibitors may be less effective [Peacock, Willett].

Regimen.

Effectiveness may depend strongly on the dosage and treatment regimen.

Treatments.

The use of other treatments may significantly affect outcomes, including anything from supplements, other medications, or other kinds of treatment such as prone positioning.

The distribution of studies will alter the outcome of a meta analysis. Consider a simplified example where everything is equal except for the treatment delay, and effectiveness decreases to zero or below with increasing delay. If there are many studies using very late treatment, the outcome may be negative, even though the treatment may be very effective when used earlier.

In general, by combining heterogeneous studies, as all meta analyses do, we run the risk of obscuring an effect by including studies where the treatment is less effective, not effective, or harmful.

When including studies where a treatment is less effective we expect the estimated effect size to be lower than that for the optimal case. We do not a priori expect that pooling all studies will create a positive result for an effective treatment. Looking at all studies is valuable for providing an overview of all research, important to avoid cherry-picking, and informative when a positive result is found despite combining less-optimal situations. However, the resulting estimate does not apply to specific cases such as early treatment in high-risk populations.

Discussion

Publication bias.

Publishing is often biased towards positive results, however evidence suggests that there may be a negative bias for inexpensive treatments for COVID-19. Both negative and positive results are very important for COVID-19, media in many countries prioritizes negative results for inexpensive treatments (inverting the typical incentive for scientists that value media recognition), and there are many reports of difficulty publishing positive results [Boulware, Meeus, Meneguesso]. For zinc, there is currently not enough data to evaluate publication bias with high confidence.

One method to evaluate bias is to compare prospective vs. retrospective studies. Prospective studies are more likely to be published regardless of the result, while retrospective studies are more likely to exhibit bias. For example, researchers may perform preliminary analysis with minimal effort and the results may influence their decision to continue. Retrospective studies also provide more opportunities for the specifics of data extraction and adjustments to influence results.

70% of retrospective studies report a statistically significant positive effect for one or more outcomes, compared to 50% of prospective studies, consistent with a bias toward publishing positive results. The median effect size for retrospective studies is 37% improvement, compared to 13% for prospective studies, suggesting a potential bias towards publishing results showing higher efficacy. Figure 20 shows a scatter plot of results for prospective and retrospective treatment studies.

Funnel plot analysis.

Funnel plots have traditionally been used for analyzing publication bias. This is invalid for COVID-19 acute treatment trials — the underlying assumptions are invalid, which we can demonstrate with a simple example. Consider a set of hypothetical perfect trials with no bias. Figure 21 plot A shows a funnel plot for a simulation of 80 perfect trials, with random group sizes, and each patient’s outcome randomly sampled (10% control event probability, and a 30% effect size for treatment). Analysis shows no asymmetry (p > 0.05). In plot B, we add a single typical variation in COVID-19 treatment trials — treatment delay. Consider that efficacy varies from 90% for treatment within 24 hours, reducing to 10% when treatment is delayed 3 days. In plot B, each trial’s treatment delay is randomly selected. Analysis now shows highly significant asymmetry, p < 0.0001, with six variants of Egger’s test all showing p < 0.05 [Egger, Harbord, Macaskill, Moreno, Peters, Rothstein, Rücker, Stanley]. Note that these tests fail even though treatment delay is uniformly distributed. In reality treatment delay is more complex — each trial has a different distribution of delays across patients, and the distribution across trials may be biased (e.g., late treatment trials may be more common). Similarly, many other variations in trials may produce asymmetry, including dose, administration, duration of treatment, differences in SOC, comorbidities, age, variants, and bias in design, implementation, analysis, and reporting.

Conflicts of interest.

Pharmaceutical drug trials often have conflicts of interest whereby sponsors or trial staff have a financial interest in the outcome being positive. Zinc for COVID-19 lacks this because it is an inexpensive and widely available supplement. In contrast, most COVID-19 zinc trials have been run by physicians on the front lines with the primary goal of finding the best methods to save human lives and minimize the collateral damage caused by COVID-19. While pharmaceutical companies are careful to run trials under optimal conditions (for example, restricting patients to those most likely to benefit, only including patients that can be treated soon after onset when necessary, and ensuring accurate dosing), not all zinc trials represent the optimal conditions for efficacy.

Early/late vs. mild/moderate/severe.

Some analyses classify treatment based on early/late administration (as we do here), while others distinguish between mild/moderate/severe cases. We note that viral load does not indicate degree of symptoms — for example patients may have a high viral load while being asymptomatic. With regard to treatments that have antiviral properties, timing of treatment is critical — late administration may be less helpful regardless of severity.

Notes.

1 of the 28 studies compare against other treatments, which may reduce the effect seen. 6 of 28 studies combine treatments. The results of zinc alone may differ. 2 of 6 RCTs use combined treatment.

Conclusion

Zinc is an effective treatment for COVID-19. Statistically significant improvements are seen for mortality, ventilation, hospitalization, and progression. 11 studies from 11 independent teams in 6 different countries show statistically significant improvements in isolation (8 for the most serious outcome). Meta analysis using the most serious outcome reported shows 32% [17 45%] improvement. Results are similar for Randomized Controlled Trials, similar after exclusions, similar for peer-reviewed studies, and similar after excluding studies using combined treatment. Early treatment is more effective than late treatment. Sufficiency studies, analyzing outcomes based on serum levels, show 74% [58 84%] improvement for patients with higher zinc levels (9 studies). Results are robust — in exclusion sensitivity analysis 11 of 28 studies must be excluded to avoid finding statistically significant efficacy in pooled analysis.

6 studies use combined treatments. When excluding those studies, the pooled improvement is 27% [11 40%] compared to 32% [17 45%].

Early treatment results are dominated by [Thomas], however this study used a low dose and was conducted in a location with low levels of zinc deficiency.

Appendix 1. Methods and Study Results

We performed ongoing searches of PubMed, medRxiv, ClinicalTrials.gov, The Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, Collabovid, Research Square, ScienceDirect, Oxford University Press, the reference lists of other studies and meta-analyses, and submissions to the site c19zinc.com. Search terms were zinc, filtered for papers containing the terms COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, or coronavirus. Automated searches are performed every few hours with notification of new matches. All studies regarding the use of zinc for COVID-19 that report a comparison with a control group are included in the main analysis. Sensitivity analysis is performed, excluding studies with major issues, epidemiological studies, and studies with minimal available information. This is a living analysis and is updated regularly.

We extracted effect sizes and associated data from all studies. If studies report multiple kinds of effects then the most serious outcome is used in pooled analysis, while other outcomes are included in the outcome specific analyses. For example, if effects for mortality and cases are both reported, the effect for mortality is used, this may be different to the effect that a study focused on. If symptomatic results are reported at multiple times, we used the latest time, for example if mortality results are provided at 14 days and 28 days, the results at 28 days are used. Mortality alone is preferred over combined outcomes. Outcomes with zero events in both arms were not used (the next most serious outcome is used — no studies were excluded). For example, in low-risk populations with no mortality, a reduction in mortality with treatment is not possible, however a reduction in hospitalization, for example, is still valuable. Clinical outcome is considered more important than PCR testing status. When basically all patients recover in both treatment and control groups, preference for viral clearance and recovery is given to results mid-recovery where available (after most or all patients have recovered there is no room for an effective treatment to do better). If only individual symptom data is available, the most serious symptom has priority, for example difficulty breathing or low SpO2 is more important than cough. When results provide an odds ratio, we computed the relative risk when possible, or converted to a relative risk according to [Zhang]. Reported confidence intervals and p-values were used when available, using adjusted values when provided. If multiple types of adjustments are reported including propensity score matching (PSM), the PSM results are used. Adjusted primary outcome results have preference over unadjusted results for a more serious outcome when the adjustments significantly alter results. When needed, conversion between reported p-values and confidence intervals followed [Altman, Altman (B)], and Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate p-values for event data. If continuity correction for zero values is required, we use the reciprocal of the opposite arm with the sum of the correction factors equal to 1 [Sweeting]. Results are expressed with RR < 1.0 favoring treatment, and using the risk of a negative outcome when applicable (for example, the risk of death rather than the risk of survival). If studies only report relative continuous values such as relative times, the ratio of the time for the treatment group versus the time for the control group is used. Calculations are done in Python (3.9.12) with scipy (1.8.0), pythonmeta (1.26), numpy (1.22.2), statsmodels (0.14.0), and plotly (5.6.0).

Forest plots are computed using PythonMeta [Deng] with the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model (the fixed effect assumption is not plausible in this case) and inverse variance weighting. Mixed-effects meta-regression results are computed with R (4.1.2) using the metafor (3.0-2) and rms (6.2-0) packages, and using the most serious sufficiently powered outcome.

We received no funding, this research is done in our spare time. We have no affiliations with any pharmaceutical companies or political parties.

We have classified studies as early treatment if most patients are not already at a severe stage at the time of treatment (for example based on oxygen status or lung involvement), and treatment started within 5 days of the onset of symptoms. If studies contain a mix of early treatment and late treatment patients, we consider the treatment time of patients contributing most to the events (for example, consider a study where most patients are treated early but late treatment patients are included, and all mortality events were observed with late treatment patients). We note that a shorter time may be preferable. Antivirals are typically only considered effective when used within a shorter timeframe, for example 0-36 or 0-48 hours for oseltamivir, with longer delays not being effective [McLean, Treanor].

A summary of study results is below. Please submit updates and corrections at the bottom of this page.

Early treatment

Effect extraction follows pre-specified rules as detailed above and gives priority to more serious outcomes. For pooled analyses, the first (most serious) outcome is used, which may differ from the effect a paper focuses on. Other outcomes are used in outcome specific analyses.

| [Asimi], 5/22/2021, retrospective, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Europe, preprint, 3 authors, this trial uses multiple treatments in the treatment arm (combined with vitamin D and selenium) – results of individual treatments may vary, excluded in exclusion analyses: excessive unadjusted differences between groups. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of mechanical ventilation, 97.4% lower, RR 0.03, p < 0.001, treatment 0 of 270 (0.0%), control 9 of 86 (10.5%), NNT 9.6, relative risk is not 0 because of continuity correction due to zero events (with reciprocal of the contrasting arm), unadjusted. |

| risk of hospitalization, 99.0% lower, RR 0.010, p < 0.001, treatment 0 of 270 (0.0%), control 24 of 86 (27.9%), NNT 3.6, relative risk is not 0 because of continuity correction due to zero events (with reciprocal of the contrasting arm), unadjusted. | |

| risk of severe case, 99.5% lower, RR 0.005, p < 0.001, treatment 0 of 270 (0.0%), control 51 of 86 (59.3%), NNT 1.7, relative risk is not 0 because of continuity correction due to zero events (with reciprocal of the contrasting arm), unadjusted. | |

| [Derwand], 7/3/2020, retrospective, USA, North America, peer-reviewed, 3 authors, this trial uses multiple treatments in the treatment arm (combined with HCQ and azithromycin) – results of individual treatments may vary. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 79.4% lower, RR 0.21, p = 0.12, treatment 1 of 141 (0.7%), control 13 of 377 (3.4%), NNT 37, odds ratio converted to relative risk. |

| risk of hospitalization, 81.6% lower, RR 0.18, p < 0.001, treatment 4 of 141 (2.8%), control 58 of 377 (15.4%), NNT 8.0, odds ratio converted to relative risk. | |

| [Mayberry], 12/16/2021, retrospective, USA, North America, peer-reviewed, 14 authors, study period March 2020 – April 2021. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 53.5% lower, OR 0.47, p < 0.001, treatment 938, control 1,090, adjusted per study, multivariable, RR approximated with OR. |

| risk of mechanical ventilation, 64.2% lower, OR 0.36, p < 0.001, treatment 938, control 1,090, adjusted per study, multivariable, RR approximated with OR. | |

| risk of ICU admission, 60.0% lower, OR 0.40, p < 0.001, treatment 938, control 1,090, adjusted per study, multivariable, RR approximated with OR. | |

| death/ventilation/ICU, 57.8% lower, OR 0.42, p < 0.001, treatment 938, control 1,090, adjusted per study, multivariable, RR approximated with OR. | |

| progression to ARDS, 85.4% lower, OR 0.15, p < 0.001, treatment 938, control 1,090, adjusted per study, multivariable, RR approximated with OR. | |

| [Thomas], 2/12/2021, Randomized Controlled Trial, USA, North America, peer-reviewed, 11 authors. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of hospitalization, 43.7% higher, RR 1.44, p = 0.72, treatment 5 of 58 (8.6%), control 3 of 50 (6.0%). |

| recovery time, 11.9% lower, relative time 0.88, p = 0.38, treatment mean 5.9 (±4.9) n=58, control mean 6.7 (±4.4) n=50, mean time to a 50% reduction in symptoms. |

Late treatment

Effect extraction follows pre-specified rules as detailed above and gives priority to more serious outcomes. For pooled analyses, the first (most serious) outcome is used, which may differ from the effect a paper focuses on. Other outcomes are used in outcome specific analyses.

| [Abd-Elsalam], 11/29/2020, Randomized Controlled Trial, Egypt, Africa, peer-reviewed, 10 authors. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 1.0% lower, RR 0.99, p = 0.99, treatment 5 of 96 (5.2%), control 5 of 95 (5.3%), NNT 1824. |

| risk of mechanical ventilation, 34.0% lower, RR 0.66, p = 0.54, treatment 4 of 96 (4.2%), control 6 of 95 (6.3%), NNT 47. | |

| risk of no recovery, 5.8% lower, RR 0.94, p = 0.97, treatment 20 of 96 (20.8%), control 21 of 95 (22.1%), NNT 79. | |

| hospitalization time, 3.6% lower, relative time 0.96, p = 0.55, treatment 96, control 95. | |

| [Al Sulaiman], 6/7/2021, retrospective, propensity score matching, Saudi Arabia, Middle East, peer-reviewed, 10 authors, study period 1 March, 2020 – 31 March, 2021. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 36.0% lower, HR 0.64, p = 0.11, treatment 23 of 82 (28.0%), control 32 of 82 (39.0%), NNT 9.1, adjusted per study, in-hospital, PSM, multivariable Cox proportional hazards. |

| risk of death, 48.0% lower, HR 0.52, p = 0.03, treatment 19 of 82 (23.2%), control 31 of 82 (37.8%), NNT 6.8, adjusted per study, 30 day, PSM, multivariable Cox proportional hazards. | |

| ICU time, 25.0% higher, relative time 1.25, p = 0.28, treatment 82, control 82. | |

| hospitalization time, 6.2% higher, relative time 1.06, p = 0.61, treatment 82, control 82. | |

| [Assiri], 8/28/2021, retrospective, Saudi Arabia, Middle East, peer-reviewed, 8 authors, excluded in exclusion analyses: unadjusted results with no group details. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 80.8% higher, RR 1.81, p = 0.44, treatment 10 of 60 (16.7%), control 4 of 58 (6.9%), odds ratio converted to relative risk. |

| [Carlucci], 5/8/2020, retrospective, USA, North America, peer-reviewed, 6 authors. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death/hospice, 37.7% lower, RR 0.62, p = 0.002, treatment 54 of 411 (13.1%), control 119 of 521 (22.8%), NNT 10, adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk, multivariate logistic regression. |

| risk of mechanical ventilation, 18.0% lower, RR 0.82, p = 0.40, treatment 29 of 411 (7.1%), control 62 of 521 (11.9%), adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk, multivariate logistic regression. | |

| risk of ICU admission, 23.5% lower, RR 0.77, p = 0.17, treatment 38 of 411 (9.2%), control 82 of 521 (15.7%), adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk, multivariate logistic regression. | |

| [Darban], 12/15/2020, Randomized Controlled Trial, Iran, Middle East, peer-reviewed, 8 authors, this trial uses multiple treatments in the treatment arm (combined with melatonin and vitamin C) – results of individual treatments may vary. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of progression, 33.3% lower, RR 0.67, p = 1.00, treatment 2 of 10 (20.0%), control 3 of 10 (30.0%), NNT 10. |

| ICU time, 6.0% lower, relative time 0.94, p = 0.30, treatment 10, control 10. | |

| [Elavarasi], 8/12/2021, retrospective, India, South Asia, preprint, 26 authors. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 65.1% lower, RR 0.35, p < 0.001, treatment 486, control 1,201, adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk, model 4, multivariate logistic regression, control prevalence approximated with overall prevalence. |

| [Frontera], 10/26/2020, retrospective, propensity score matching, USA, North America, preprint, median age 64.0, 14 authors, this trial uses multiple treatments in the treatment arm (combined with HCQ) – results of individual treatments may vary. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 37.0% lower, HR 0.63, p = 0.01, treatment 121 of 1,006 (12.0%), control 424 of 2,467 (17.2%), NNT 19, adjusted per study, PSM. |

| risk of death, 24.0% lower, HR 0.76, p = 0.02, treatment 121 of 1,006 (12.0%), control 424 of 2,467 (17.2%), NNT 19, adjusted per study, regression. | |

| [Gadhiya], 4/8/2021, retrospective, USA, North America, peer-reviewed, 4 authors, excluded in exclusion analyses: substantial unadjusted confounding by indication likely. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 40.9% higher, RR 1.41, p = 0.33, treatment 21 of 54 (38.9%), control 34 of 229 (14.8%), adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk, multivariate logistic regression. |

| [Kaplan], 10/1/2021, Randomized Controlled Trial, USA, North America, preprint, 12 authors, study period 21 September, 2020 – 22 January, 2021, average treatment delay 5.9 days, this trial uses multiple treatments in the treatment arm (combined with resveratrol) – results of individual treatments may vary. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of mechanical ventilation, 14.3% higher, RR 1.14, p = 1.00, treatment 1 of 14 (7.1%), control 1 of 16 (6.2%). |

| risk of ICU admission, 14.3% higher, RR 1.14, p = 1.00, treatment 1 of 14 (7.1%), control 1 of 16 (6.2%). | |

| risk of hospitalization, 14.3% higher, RR 1.14, p = 1.00, treatment 1 of 14 (7.1%), control 1 of 16 (6.2%). | |

| [Krishnan], 7/20/2020, retrospective, USA, North America, peer-reviewed, 13 authors, excluded in exclusion analyses: unadjusted results with no group details. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 17.6% lower, RR 0.82, p = 0.18, treatment 31 of 58 (53.4%), control 61 of 94 (64.9%), NNT 8.7. |

| [Mulhem], 4/7/2021, retrospective, database analysis, USA, North America, peer-reviewed, 3 authors, excluded in exclusion analyses: substantial unadjusted confounding by indication likely, substantial confounding by time likely due to declining usage over the early stages of the pandemic when overall treatment protocols improved dramatically. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 45.6% lower, RR 0.54, p < 0.001, treatment 256 of 1,596 (16.0%), control 260 of 1,623 (16.0%), adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk, logistic regression. |

| [Patel], 2/25/2021, Double Blind Randomized Controlled Trial, Australia, Oceania, peer-reviewed, 12 authors. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 20.0% lower, RR 0.80, p = 1.00, treatment 2 of 15 (13.3%), control 3 of 18 (16.7%), NNT 30. |

| [Yao], 7/22/2020, retrospective, USA, North America, peer-reviewed, 9 authors. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 34.0% lower, RR 0.66, p = 0.09, treatment 73 of 196 (37.2%), control 21 of 46 (45.7%), adjusted per study, multivariate Cox regression. |

Prophylaxis

Effect extraction follows pre-specified rules as detailed above and gives priority to more serious outcomes. For pooled analyses, the first (most serious) outcome is used, which may differ from the effect a paper focuses on. Other outcomes are used in outcome specific analyses.

| [Abdulateef], 4/8/2021, retrospective, Iraq, Middle East, peer-reviewed, 7 authors, study period July 2020 – August 2020, excluded in exclusion analyses: unadjusted results with no group details. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of hospitalization, 13.1% lower, RR 0.87, p = 0.83, treatment 7 of 111 (6.3%), control 23 of 317 (7.3%), NNT 105, unadjusted. |

| [Bagheri], 9/1/2021, retrospective, Iran, Middle East, peer-reviewed, 6 authors. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of progression, 60.4% lower, OR 0.40, p = 0.41, treatment 33, control 477, adjusted per study, multinomial logistic regression, RR approximated with OR. |

| risk of being in the hospitalized vs. outpatient group, 41.0% lower, RR 0.59, p = 0.37, treatment 4 of 33 (12.1%), control 167 of 477 (35.0%), NNT 4.4, adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk, binary logistic regression. | |

| [Gordon], 12/13/2021, prospective, USA, North America, peer-reviewed, 2 authors. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 67.6% lower, RR 0.32, p = 0.48, treatment 0 of 104 (0.0%), control 1 of 96 (1.0%), NNT 96, relative risk is not 0 because of continuity correction due to zero events (with reciprocal of the contrasting arm). |

| risk of symptomatic case, 85.3% lower, RR 0.15, p = 0.02, treatment 2 of 104 (1.9%), control 9 of 96 (9.4%), NNT 13, adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk. | |

| [Holt], 3/30/2021, prospective, United Kingdom, Europe, peer-reviewed, 34 authors, study period 1 May, 2020 – 5 February, 2021, excluded in exclusion analyses: significant unadjusted confounding possible. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of case, 6.8% lower, RR 0.93, p = 0.77, treatment 21 of 750 (2.8%), control 425 of 14,477 (2.9%), NNT 737, adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk, minimally adjusted, group sizes approximated. |

| [Israel], 7/27/2021, retrospective, Israel, Middle East, peer-reviewed, 10 authors, this trial uses multiple treatments in the treatment arm (combined with calcium) – results of individual treatments may vary, excluded in exclusion analyses: treatment or control group size extremely small. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of hospitalization, >99.9% lower, RR <0.001, p = 0.04, treatment 0 of 10 (0.0%), control 6,953 of 20,849 (33.3%), NNT 3.0, odds ratio converted to relative risk, relative risk is not 0 because of continuity correction due to zero events (with reciprocal of the contrasting arm), PCR+, cohort 2. |

| [Kumar], 2/23/2022, retrospective, India, South Asia, peer-reviewed, 10 authors, study period June 2021 – August 2021, excluded in exclusion analyses: unadjusted results with no group details. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of death, 20.0% lower, RR 0.80, p = 0.71, treatment 6 of 75 (8.0%), control 3 of 30 (10.0%), NNT 50, unadjusted. |

| [Louca], 11/30/2020, retrospective, United Kingdom, Europe, peer-reviewed, 26 authors. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of case, 0.9% lower, RR 0.99, p = 0.80, odds ratio converted to relative risk, United Kingdom, all adjustment model. |

| [Mahto], 2/15/2021, retrospective, India, South Asia, peer-reviewed, 6 authors. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of IgG positive, 36.8% lower, RR 0.63, p = 0.35, treatment 10 of 38 (26.3%), control 83 of 651 (12.7%), adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk, multivariable. |

| [Nimer], 2/28/2022, retrospective, Jordan, Middle East, peer-reviewed, survey, 4 authors, study period March 2021 – July 2021. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of hospitalization, 25.4% higher, RR 1.25, p = 0.21, treatment 41 of 326 (12.6%), control 178 of 1,822 (9.8%), adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk, multivariable. |

| risk of severe case, 13.0% higher, RR 1.13, p = 0.46, treatment 46 of 326 (14.1%), control 214 of 1,822 (11.7%), adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk, multivariable. | |

| [Seet], 4/14/2021, Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial, Singapore, Asia, peer-reviewed, 15 authors, this trial compares with another treatment – results may be better when compared to placebo. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of symptomatic case, 49.7% lower, RR 0.50, p < 0.001, treatment 33 of 634 (5.2%), control 64 of 619 (10.3%), NNT 19. |

| risk of case, 26.9% lower, RR 0.73, p = 0.03, treatment 300 of 634 (47.3%), control 433 of 619 (70.0%), NNT 4.4, adjusted per study, odds ratio converted to relative risk, model 6. | |

| [Shehab], 2/28/2022, retrospective, multiple countries, multiple regions, peer-reviewed, survey, 7 authors, study period September 2020 – March 2021, excluded in exclusion analyses: unadjusted results with no group details. Submit Corrections or Updates. | risk of severe case, 47.4% lower, RR 0.53, p = 0.24, treatment 4 of 65 (6.2%), control 22 of 188 (11.7%), NNT 18, unadjusted, severe vs. mild cases. |

References

1.

Abd-Elsalam et al., Biological Trace Element Research, doi:10.1007/s12011-020-02512-1, Do Zinc Supplements Enhance the Clinical Efficacy of Hydroxychloroquine?: a Randomized, Multicenter Trial, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12011-020-02512-1.

2.

Abdulateef et al., Open Medicine, doi:10.1515/med-2021-0273, COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use, https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/med-2021-0273/html.

3.

academic.oup.com, https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/110/1/76/5510583.

4.

Al Sulaiman et al., Critical Care, doi:10.1186/s13054-021-03785-1 (preprint 6/7/2021), Evaluation of Zinc Sulfate as an Adjunctive Therapy in COVID-19 Critically Ill Patients: a Two Center Propensity-score Matched Study, https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13054-021-03785-1.

5.

Altman, D., BMJ, doi:10.1136/bmj.d2304, How to obtain the P value from a confidence interval, https://www.bmj.com/content/343/bmj.d2304.

6.

Altman (B) et al., BMJ, doi:10.1136/bmj.d2090, How to obtain the confidence interval from a P value, https://www.bmj.com/content/343/bmj.d2090.

7.

Anglemyer et al., Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 4, doi:10.1002/14651858.MR000034.pub2, Healthcare outcomes assessed with observational study designs compared with those assessed in randomized trials, https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cd..0.1002/14651858.MR000034.pub2/full.

8.

Asimi et al., Endocrine Abstracts, doi:10.1530/endoabs.73.PEP14.2, Selenium, zinc, and vitamin D supplementation affect the clinical course of COVID-19 infection in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, https://www.endocrine-abstracts.org/ea/0073/ea0073pep14.2.

9.

Assiri et al., Journal of Infection and Public Health, doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2021.08.030, COVID-19 related treatment and outcomes among COVID-19 ICU patients: A retrospective cohort study, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876034121002495.

10.

Bagheri et al., Journal of Family & Reproductive Health, doi:10.18502/jfrh.v14i3.4668 , Supplement Usage Pattern in a Group of COVID- 19 Patients in Tehran, https://europepmc.org/article/PMC/PMC7868648.

11.

Boulware, D., Comments regarding paper rejection, https://twitter.com/boulware_dr/status/1311331372884205570.

12.

Carlucci et al., J. Med. Microbiol., Sep 15, 2020, doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001250 (preprint 5/8), Zinc sulfate in combination with a zinc ionophore may improve outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, https://www.microbiologyresearch.o..t/journal/jmm/10.1099/jmm.0.001250.

13.

Concato et al., NEJM, 342:1887-1892, doi:10.1056/NEJM200006223422507, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejm200006223422507.

14.

Darban et al., Journal of Cellular & Molecular Anesthesia, doi:10.22037/jcma.v6i2.32182, Efficacy of High Dose Vitamin C, Melatonin and Zinc in Iranian Patients with Acute Respiratory Syndrome due to Coronavirus Infection: A Pilot Randomized Trial, https://journals.sbmu.ac.ir/jcma/article/view/32182.

15.

Deaton et al., Social Science & Medicine, 210, doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.005, Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953617307359.

16.

Deng, H., PyMeta, Python module for meta-analysis, http://www.pymeta.com/.

17.

Derwand et al., International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106214 (preprint 7/3), COVID-19 Outpatients – Early Risk-Stratified Treatment with Zinc Plus Low Dose Hydroxychloroquine and Azithromycin: A Retrospective Case Series Study, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924857920304258.

18.

Du Laing et al., Nutrients, doi:10.3390/nu13103304, Course and Survival of COVID-19 Patients with Comorbidities in Relation to the Trace Element Status at Hospital Admission, https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/10/3304.

19.

Egger et al., BMJ, doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629, Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test, https://syndication.highwire.org/content/doi/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

20.

Ekemen Keleş et al., European Journal of Pediatrics, doi:10.1007/s00431-021-04348-w, Serum zinc levels in pediatric patients with COVID-19, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00431-021-04348-w.

21.

Elavarasi et al., medRxiv, doi:10.1101/2021.08.10.21261855, Clinical features, demography and predictors of outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a tertiary care hospital in India – a cohort study, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.08.10.21261855v1.

22.

Faria et al., Science, doi:10.1126/science.abh2644, Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil, https://www.science.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/science.abh2644.

23.

Fromonot et al., Clinical Nutrition, doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2021.04.042, Hypozincemia in the early stage of COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk of severe COVID-19, https://www.clinicalnutritionjourn..cle/S0261-5614(21)00234-X/fulltext.

24.

Frontera et al., Research Square, doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-94509/v1, Treatment with Zinc is Associated with Reduced In-Hospital Mortality Among COVID-19 Patients: A Multi-Center Cohort Study, https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-94509/v1.

25.

Gadhiya et al., BMJ Open, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042549, Clinical characteristics of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 and the impact on mortality: a single-network, retrospective cohort study from Pennsylvania state, https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/11/4/e042549.info.

26.

Gonçalves et al., Nutrition in Clinical Practice, doi:10.1002/ncp.10612, Association Between Low Zinc Levels and Severity of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome by New Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, https://aspenjournals.onlinelibrar..ley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ncp.10612.

27.

Gordon et al., Frontiers in Medicine, doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.756707, A Case-Control Study for the Effectiveness of Oral Zinc in the Prevention and Mitigation of COVID-19, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.756707/full.

28.

Harbord et al., Statistics in Medicine, doi:10.1002/sim.2380, A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints, https://api.wiley.com/onlinelibrary/tdm/v1/articles/10.1002%2Fsim.2380.

29.

Holt et al., Thorax, doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-217487, Risk factors for developing COVID-19: a population-based longitudinal study (COVIDENCE UK), https://thorax.bmj.com/content/early/2021/11/02/thoraxjnl-2021-217487.

30.

Israel et al., Epidemiology and Global Health Microbiology and Infectious Disease, doi:10.7554/eLife.68165, Identification of drugs associated with reduced severity of COVID-19: A case-control study in a large population, https://elifesciences.org/articles/68165.

31.

Jadad et al., doi:10.1002/9780470691922, Randomized Controlled Trials: Questions, Answers, and Musings, Second Edition, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9780470691922.

32.

Jothimani, COVID-19: Poor outcomes in patients with zinc deficiency, https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(20)30730-X/fulltext.

33.

journalofinfection.com, https://www.journalofinfection.com..cle/S0163-4453(21)00654-X/fulltext.

34.

Kaplan et al., SSRN, 10.2139/ssrn.3934228, Resveratrol and Zinc in the Treatment of Outpatients With COVID-19 – The Reszinate Study – A Phase 1/2 Randomized Clinical Trial Utilizing Home Patient-Obtained Nasal and Saliva Viral Sampling, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3934228.

35.

Karita et al., medRxiv, doi:10.1101/2021.08.27.21262754, Trajectory of viral load in a prospective population-based cohort with incident SARS-CoV-2 G614 infection, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.08.27.21262754v1.

36.

Krishnan et al., J Clin Anesth., doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.110005, Clinical comorbidities, characteristics, and outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients in the State of Michigan with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7369577/.

37.

Kumar et al., Cureus, doi:10.7759/cureus.22528, Role of Zinc and Clinicopathological Factors for COVID-19-Associated Mucormycosis (CAM) in a Rural Hospital of Central India: A Case-Control Study, https://www.cureus.com/articles/87..central-india-a-case-control-study.

38.

Lee et al., Arch Intern Med., 2011, 171:1, 18-22, doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.482, Analysis of Overall Level of Evidence Behind Infectious Diseases Society of America Practice Guidelines, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/j..nternalmedicine/fullarticle/226373.

39.

López-Medina et al., JAMA, doi:10.1001/jama.2021.3071, Effect of Ivermectin on Time to Resolution of Symptoms Among Adults With Mild COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2777389.

40.

Louca et al., BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health, doi:10.1136/bmjnph-2021-000250 (preprint 11/30/20), Modest effects of dietary supplements during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from 445 850 users of the COVID-19 Symptom Study app, https://nutrition.bmj.com/content/4/1/149.

41.

Macaskill et al., Statistics in Medicine, doi:10.1002/sim.698, A comparison of methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis, https://api.wiley.com/onlinelibrary/tdm/v1/articles/10.1002%2Fsim.698.

42.

Mahto et al., American Journal of Blood Research, 11:1, Seroprevalence of IgG against SARS-CoV-2 and its determinants among healthcare workers of a COVID-19 dedicated hospital of India, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC8010601/.

43.

Mayberry et al., Critical Care Medicine, doi:10.1097/01.ccm.0000807104.82650.d6, Zinc use is associated with improved outcomes in COVID-19: results from the CRUSH-COVID registry, https://journals.lww.com/ccmjourna..ED_WITH_IMPROVED_OUTCOMES.161.aspx.

44.

McLean et al., Open Forum Infect. Dis. September 2015, 2:3, doi:10.1093/ofid/ofv100, Impact of Late Oseltamivir Treatment on Influenza Symptoms in the Outpatient Setting: Results of a Randomized Trial, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4525010/.

45.

Meeus, G., Online Comment, https://twitter.com/gertmeeus_MD/status/1386636373889781761.

46.

Meneguesso, A., Médica defende tratamento precoce da Covid-19, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X5FCrIm_19U.

47.

Moreno et al., BMC Medical Research Methodology, doi:10.1186/1471-2288-9-2, Assessment of regression-based methods to adjust for publication bias through a comprehensive simulation study, http://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-2288-9-2/fulltext.html.

48.

Mulhem et al., BMJ Open, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042042, 3219 hospitalised patients with COVID-19 in Southeast Michigan: a retrospective case cohort study, https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/11/4/e042042.info.

49.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3510072/.

50.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (B), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/a..C3510072/bin/pone.0050568.s003.xls.

51.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (C), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7836617/.

52.

Nichol et al., Injury, 2010, doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.03.033, Challenging issues in randomised controlled trials, https://www.injuryjournal.com/article/S0020-1383(10)00233-0/fulltext.

53.

Nimer et al., Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences, doi:10.17305/bjbms.2021.7009, The impact of vitamin and mineral supplements usage prior to COVID-19 infection on disease severity and hospitalization, https://www.bjbms.org/ojs/index.php/bjbms/article/view/7009.

54.

Nonaka et al., International Journal of Infectious Diseases, doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.003, SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern P.1 (Gamma) infection in young and middle-aged patients admitted to the intensive care units of a single hospital in Salvador, Northeast Brazil, February 2021, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1201971221006354.

55.

Patel et al., Journal of Medical Virology, doi:10.1002/jmv.26895, A pilot double‐blind safety and feasibility randomized controlled trial of high‐dose intravenous zinc in hospitalized COVID‐19 patients, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jmv.26895.

56.

patrickholford.com, https://www.patrickholford.com/blog/vitamin-c-speeds-up-covid-recovery.

57.

Peacock et al., bioRxiv, doi:10.1101/2021.12.31.474653, The SARS-CoV-2 variant, Omicron, shows rapid replication in human primary nasal epithelial cultures and efficiently uses the endosomal route of entry, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.12.31.474653.

58.

Peters, J., JAMA, doi:10.1001/jama.295.6.676, Comparison of Two Methods to Detect Publication Bias in Meta-analysis, http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/202337.

59.

Ramos et al., Global Journal of Health Science, doi:10.5539/gjhs.v14n1p1, Vitamin D, Zinc and Iron in Adult Patients with Covid-19 and Their Action in the Immune Response as Biomarkers, https://ccsenet.org/journal/index…s/article/download/0/0/46298/49565.

60.

Rothstein, H., Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments, https://www.wiley.com/en-ae/Public..nt+and+Adjustments-p-9780470870143.

61.

Rücker et al., Statistics in Medicine, doi:10.1002/sim.2971, Arcsine test for publication bias in meta-analyses with binary outcomes, https://api.wiley.com/onlinelibrary/tdm/v1/articles/10.1002%2Fsim.2971.

62.

Seet et al., International Journal of Infectious Diseases, doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.04.035, Positive impact of oral hydroxychloroquine and povidone-iodine throat spray for COVID-19 prophylaxis: an open-label randomized trial, https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(21)00345-3/fulltext.

63.

Shehab et al., Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, doi:10.4314/tjpr.v21i2.13, Immune-boosting effect of natural remedies and supplements on progress of, and recovery from COVID-19 infection, https://www.tjpr.org/admin/12389900798187/2022_21_2_14.pdf.

64.

Stanley et al., Research Synthesis Methods, doi:10.1002/jrsm.1095, Meta-regression approximations to reduce publication selection bias, https://api.wiley.com/onlinelibrar..dm/v1/articles/10.1002%2Fjrsm.1095.

65.

Sweeting et al., Statistics in Medicine, doi:10.1002/sim.1761, What to add to nothing? Use and avoidance of continuity corrections in meta‐analysis of sparse data, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sim.1761.

66.

Thomas et al., JAMA Network Open, doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0369, Effect of High-Dose Zinc and Ascorbic Acid Supplementation vs Usual Care on Symptom Length and Reduction Among Ambulatory Patients With SARS-CoV-2 Infection: The COVID A to Z Randomized Clinical Trial, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2776305.

67.

Tomasa-Irriguible et al., Metabolites, doi:10.3390/metabo11090565 (preprint 10/26/2020), Low Levels of Few Micronutrients May Impact COVID-19 Disease Progression: An Observational Study on the First Wave, https://www.mdpi.com/2218-1989/11/9/565.

68.

Treanor et al., JAMA, 2000, 283:8, 1016-1024, doi:10.1001/jama.283.8.1016, Efficacy and Safety of the Oral Neuraminidase Inhibitor Oseltamivir in Treating Acute Influenza: A Randomized Controlled Trial, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/192425.

69.

Vogel-González et al., Nutrients, doi:10.3390/nu13020562 (preprint 10/11/2020), Low Zinc Levels at Admission Associates with Poor Clinical Outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 Infection, https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/2/562/htm.

70.

Willett et al., medRxiv, doi:10.1101/2022.01.03.21268111, The hyper-transmissible SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant exhibits significant antigenic change, vaccine escape and a switch in cell entry mechanism, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.01.03.21268111.

71.

Yao et al., Chest, doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.082, The Minimal Effect of Zinc on the Survival of Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19, https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(20)31961-9/fulltext.

72.

Yasui et al., International Journal of Infectious Diseases, doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.008, Analysis of the predictive factors for a critical illness of COVID-19 during treatment - relationship between serum zinc level and critical illness of COVID-19, https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(20)30723-2/fulltext.

73.

Yeh et al., BMJ, doi:10.1136/bmj.k5094 , Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma when jumping from aircraft: randomized controlled trial, https://www.bmj.com/content/363/bmj.k5094.

74.

Zavascki et al., Research Square, doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-910467/v1, Advanced ventilatory support and mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 caused by Gamma (P.1) variant of concern compared to other lineages: cohort study at a reference center in Brazil, https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-910467/v1.

75.

Zeraatkar et al., medRxiv, doi:10.1101/2022.04.04.22273372, The trustworthiness and impact of trial preprints for COVID-19 decision-making: A methodological study, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.04.04.22273372.

76.

Zhang et al., JAMA, 80:19, 1690, doi:10.1001/jama.280.19.1690, What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/188182.